Strategic Freight Cost Analysis: Total Landed Cost Comparison of Sea vs. Air Freight in 2025

I. Executive Summary: Strategic Cost Outlook for 2025

The question of whether sea freight or air freight saves more money in 2025 cannot be answered by a simple comparison of base transportation rates. The global logistics landscape is characterized by controlled instability, forcing sophisticated shippers to adopt a Total Landed Cost (TLC) approach. True savings are realized not through the lowest ticket price, but through minimizing the total financial burden, which heavily includes the Inventory Holding Cost (IHC).

In 2025, sea freight continues to offer the lowest base cost per kilogram or cubic meter, making it the default choice for bulk and low-value cargo. However, this advantage is being aggressively eroded by rising regulatory costs (like the EU Emissions Trading System, ETS) , persistent geopolitical risk leading to massive rate volatility , and the critical financial burden of lengthy transit times (20–50 days).

For high-value, high-demand, or time-critical goods, air freight is increasingly the economically superior option. Although air base rates are significantly higher (e.g., a $195 ocean shipment can cost $1,000 by air) , the speed of air transport (1–7 days) dramatically reduces the capital tied up in inventory. Since annual IHC typically ranges from 15% to 30% of inventory value , the opportunity cost of sea freight’s extended transit time often outweighs the air premium, effectively positioning air freight as a cash flow and risk mitigation strategy, rather than just an expedited service.

A. The Great Cost Equation: Base Rate vs. Inventory Holding Cost (IHC)

The foundation of cost optimization in 2025 rests on recognizing that the freight cost itself is only one variable in the broader TLC formula. Shippers with a low-to-moderate carrying cost percentage and non-urgent inventory will continue to find sea freight unbeatable on base price. Conversely, shippers carrying high-value inventory, such as electronics or pharmaceuticals, find that minimizing the 30-day capital lockup differential between sea and air transport yields substantial financial returns that exceed the higher air freight rate. This reframing of air transport as a financial optimization tool—rather than purely a speed upgrade—is essential for maximizing profitability in the current market environment.

B. Key Findings and Segmented Recommendations

- For Bulk/Low-Value Goods (>5 CBM / >500 kg): Sea freight remains the most cost-effective solution, provided FCL efficiency is maximized. Cost discipline must focus on minimizing new regulatory surcharges, particularly the expanding EU ETS fees, and mitigating exposure to volatile spot rate spikes.

- For High-Value/Urgent Goods (<2 CBM / Electronics/Luxury): Air freight is economically superior. Its speed saves capital tied up in inventory, allowing for quicker inventory turnover and better cash flow. Air transport is also highly recommended when the cost of shipping is less than 15% to 20% of the goods’ value.

- The New Break-Even Threshold (2-5 CBM or Medium-High Value): This intermediate segment is most vulnerable to 2025 market shifts. The complexity of Less-than-Container Load (LCL) pricing, which includes numerous handling and consolidation charges , combined with rising sea regulatory costs, means that the traditional sea freight advantage for this volume is significantly eroding. Businesses here must rely on precise TLC modeling to determine the optimal mode, as LCL may be surprisingly competitive with air freight only within a narrow volumetric window.

II. The 2025 Global Freight Market Dynamics: An Environment of Controlled Instability

The 2025 market is defined by conflicting pressures: long-term structural overcapacity driving potential deflation, countered by short-term geopolitical and operational disruptions creating periodic inflation and rate spikes. Navigating this environment requires continuous tracking of spot rates and strategic engagement with contract pricing.

A. Ocean Freight: The Paradox of Oversupply and Rate Volatility

The shipping industry is facing a fundamental contradiction. On the supply side, a large influx of new vessel deliveries is anticipated, leading to sustained overcapacity expected to peak around 2027. This structural imbalance suggests long-term downward pressure on rates, potentially mirroring the 2016 price war, assuming typical trade routes normalize.

However, the immediate 2025 reality is one of sudden rate inflation. Despite the global overcapacity threat, Q2 2025 saw alarming rate surges on major lanes, reflecting deep, structural disruptions across the maritime sector. For example, shipping a container from Shanghai to Rotterdam surged from $1,800 to $6,000+. This instability is driven by global routing disruptions, such as the rerouting necessitated by the Red Sea crisis, which temporarily absorbs excess capacity by extending transit times.

Carriers respond to the market by utilizing blank sailings as a primary tool to manage capacity and influence spot rates. As of Q3 2025, spot rates show variability: Asia-US West Coast prices hovered around $1,725 per Forty-Foot Equivalent Unit (FEU), while Asia-US East Coast prices were higher at $2,708/FEU. The Containerized Freight Index, tracking weekly spot rates, traded flat at 1403.46 points in October 2025, but this figure remains 35.78% lower than a year ago, illustrating the ongoing correction following major historical volatility.

The disparity between the long-term overcapacity forecast and the short-term rate spikes confirms that carriers are successfully leveraging market disruptions to maintain pricing power. Structural overcapacity usually depresses rates, but operational complexity, such as poor schedule adherence and global rerouting, effectively absorbs this excess capacity, translating potential deflation into periodic inflationary cost pressures. Consequently, shippers must not only budget for the average freight rate but also for the cost of disruption, which may necessitate budget allocation for expedited transport options (air freight) when ocean schedules inevitably fail.

B. Air Freight: Stabilization and Strategic Uptick

The air cargo market entered 2025 on solid footing, following a period of sustained demand growth in 2024, driven significantly by the expansion of e-commerce. The demand forecast for 2025 anticipates continued growth of +4% to +6%.

Current air rates, while historically high, show signs of stabilization due to improving capacity. In early Q1 2025, rates from Asia to the U.S. averaged $5.39 per kilogram. Later data shows China to North America weekly prices slightly moderated to $5.30/kg. The primary source of new supply (Available Cargo-Tonne-Kilometer, ACTK) is the expansion of belly cargo capacity, which increases as passenger flight routes and frequencies expand globally. This supply growth acts as a necessary counter-balance to resilient demand, helping prevent runaway spot rates.

A significant analytical point is the emerging role of air freight as a risk management tool. Volatility in U.S. tariff policies and potential changes to customs rules (such as the de minimis rule) have compelled certain companies to abandon traditional cost-cutting measures in favor of strategic modal shifts from maritime to air transport. Sea freight’s lengthy 30+ day transit time locks inventory into a potentially disadvantageous regulatory landscape, exposing companies to tariff changes that take effect mid-transit. Air freight’s speed (1–7 days) allows for quicker inventory pivots and minimizes exposure to policy uncertainty. The “cost saving” for air freight, in this context, is the mitigation of regulatory and commercial risk, a crucial financial factor often overlooked when evaluating transport expense alone.

C. Contract vs. Spot Rate Strategy (Risk Mitigation)

Navigating 2025’s volatility necessitates a sophisticated procurement strategy that utilizes both long-term contract rates and opportunistic spot rates.

Contract Rates: These rates, typically established through an annual Request for Proposal (RFP) process, offer stability and fixed pricing for committed volumes. Contract rates are essential for mitigating exposure to the sudden, unpredictable rate spikes that have characterized the volatile spot market in recent years. For strategic transatlantic routes, for instance, industry projections place average contract rates around $1,550 per TEU (Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit) for 2025, emphasizing the value of securing predictable pricing.

Spot Rates: Spot rates offer necessary agility and immediate responsiveness to real-time market changes. They are useful for managing sudden, non-forecasted demand spikes or leveraging temporary dips in carrier capacity. However, spot rates carry a higher risk of unexpected premiums, particularly on secondary trade lanes (“thin routes”) where sudden demand jumps can drive prices 40%-50% above dense-lane averages.

The optimal strategy for 2025 involves securing 70%–80% of core volume via stable contract rates and reserving the remainder for dynamic spot purchasing, ensuring continuity while maintaining flexibility.

Table: Market Volatility and Risk Mitigation Strategy (2025)

Market Dynamic Impact on Cost/Risk Mitigation Strategy

Geopolitical Disruption (e.g., Red Sea) High rate volatility; extended ocean transit times (20–50+ days) Diversify routes; Utilize air freight for urgent shipments; Maintain buffer stock

Regulatory Changes (e.g., EU ETS, Tariffs) Structural cost increase for sea freight (EU); Uncertainty for high-value air cargo Strategic modal shift (air) to minimize lead time exposure; Use favorable Incoterms (e.g., DDP)

Carrier Overcapacity (Structural) Potential long-term rate deflation Lock in favorable long-term contracts (70–80% volume) for rate stability

Fuel Price Fluctuation (BAF/AFC) Variable and unpredictable surcharges Audit BAF/AFC components; Negotiate fuel price caps in contracts

III. Comprehensive Cost Component Breakdown: Analyzing the All-In Price

An accurate comparison requires moving beyond the base rate to dissect the highly variable, mandatory, and regulatory costs that determine the final freight expenditure.

A. Base Freight Cost Calculation Methodology

The fundamental difference between sea and air pricing lies in their density ratios and cost basis.

1. Ocean Freight (FCL vs. LCL)

Sea freight utilizes two primary structures: Full Container Load (FCL) and Less-than-Container Load (LCL). FCL is priced at a fixed, flat rate per container type (20-foot, 40-foot, or high cube), regardless of how full it is. This structure offers exponential savings when cargo volume is optimized. The tipping point for upgrading from LCL to FCL—and thus leveraging these scale economies—is typically around 15 cubic meters (CBM).

LCL is charged either per CBM or per 1,000 kilograms, whichever yields the higher rate, and includes additional fees for consolidation, handling, and documentation.For mode comparison, shipments exceeding 5 CBM overwhelmingly favor sea freight.

2. Air Freight (Chargeable Weight)

Air freight utilizes the concept of Chargeable Weight to ensure efficient use of space and weight capacity. The chargeable weight is always the greater of the shipment’s Actual Weight or its Volumetric (Dimensional) Weight.

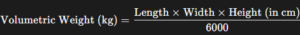

The standard formula for calculating volumetric weight, established by the International Air Transport Association (IATA), uses a fixed density ratio:

This calculation ensures that light but bulky cargo is priced based on the space it consumes, penalizing inefficient packaging.5 The total air freight cost is calculated as:

![]()

B. Analysis of Mandatory Carrier Surcharges

Surcharges are critical cost components that significantly inflate the final freight price beyond the initial base rate quote.

- Fuel Adjustments (BAF/AFC): The Bunker Adjustment Factor (BAF) for ocean freight and the Air Fuel Surcharge (AFC) compensate carriers for volatile fuel prices. For maritime transport, the BAF is tied to the price index of low-sulfur fuel oil (VLSFO). Market analysis suggests diesel prices will be 3% to 5% lower on average in 2025 than in 2024, decreasing in the first half but rebounding in the second. This volatility requires carriers to issue frequent BAF revisions. For air freight departing from Japan, for example, fuel surcharges as of August 2025 ranged from JPY 51/Kg to JPY 72/Kg, depending on the destination territory.

- Terminal Handling Charges (THC): These are fixed, non-negotiable fees charged by port authorities at both origin and destination for container handling. Port-level surcharges, which include THC, documentation fees, and wharfage, can quietly add $200 to $500 or more per container. Strategic use of Incoterms is necessary to assign responsibility for these unavoidable costs.

- Seasonal and Geopolitical Surcharges (PSS, CAF): Carriers routinely implement Peak Season Surcharges (PSS), particularly during the Q3 build-up to the holiday season. Confirmed PSS increases, such as those implemented from Far East Asia to Oceania effective August 2025, must be modeled into Q3/Q4 logistics budgets. Additionally, the Currency Adjustment Factor (CAF) compensates carriers for exchange rate fluctuations, further increasing cost variability on international routes.

C. The New Regulatory Cost Headwind: EU ETS

A major structural cost increase affecting sea freight in 2025 is the continued phase-in of the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). This regulation mandates that shipping companies calling at EU/EEA ports surrender allowances for emissions.

The cost to comply is expected to rise significantly because the phase-in requires carriers to surrender allowances for 70% of their reported emissions in 2025, a substantial increase from the 40% required in 2024. Furthermore, the market price of European allowances is expected to increase due to supply cuts. This combination of higher compliance percentage and potentially higher allowance prices is estimated to nearly double the emission surcharge in 2025 compared to 2024.

This influx of high, mandatory regulatory fees creates a structural cost compression point. The base rate advantage of sea freight is diminished by these costs on major Asia-Europe trade lanes. The resulting narrowing of the financial gap between air and sea freight for medium-value goods may push more risk-averse shippers toward air freight, viewing its higher base price as acceptable given the mitigation of volatile BAF/THC costs and the avoidance of high, fixed environmental surcharges.

Table: Ocean Freight Hidden Surcharges and Regulatory Costs (2025 Estimates)

| Surcharge Type | Mechanism | Quantified Impact (Per Container) | Implication for Savings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terminal Handling Charge (THC) | Port handling of containers (fixed fee) | Adds $200–$500+ per container | Non-negotiable, must be managed via Incoterms. |

| Bunker Adjustment Factor (BAF) | Fluctuations in VLSFO fuel prices | Variable; subject to expected H2 2025 diesel price rebound | Introduces cost volatility; must be audited. |

| Peak Season Surcharge (PSS) | Increased Q3/Q4 demand | Confirmed increases effective Q3 2025 | Mandatory seasonal budget spike. |

| EU ETS Regulatory Surcharge | Mandatory emissions allowance purchase | Estimated to nearly double 2024 costs | Structural, long-term increase that erodes sea freight’s relative cost advantage, particularly on European route |

IV. The Total Landed Cost (TLC) Model: The True Measure of Savings

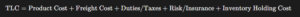

The ultimate metric for determining true cost-effectiveness is the Total Landed Cost (TLC), which recognizes that freight cost is inextricably linked to inventory finance costs.

A. Deconstructing Inventory Holding Cost (IHC)

Inventory Holding Cost (IHC), also known as carrying cost, encompasses all expenses associated with storing and financing unsold inventory. For high-value goods, IHC is the primary financial lever that can justify the air freight premium.

IHC is calculated based on four main component costs:

- Capital Cost: The opportunity cost of capital tied up in stock until the goods are sold.

- Storage Cost: Expenses related to warehouse space, utilities, labor, and equipment.

- Risk Cost: Financial losses due to obsolescence, shrinkage, and insurance against damage or loss.

- Inventory Service Costs: Costs like taxes and insurance premiums specific to the inventory.

Industry benchmarks estimate that annual IHC typically ranges between 15% and 30% of the total inventory value.

B. Transit Time vs. Inventory Holding Cost Calculation

The differential in transit time—30 days or more—is the financial catalyst favoring air freight for high-value goods.

Sea freight typically incurs transit times between 20 and 50 days , which are currently subject to high variability due to congestion and geopolitical rerouting. Conversely, air freight transit time is generally 1 to 7 days globally.

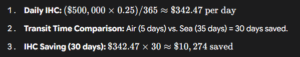

Consider a hypothetical high-value shipment (e.g., consumer electronics) valued at $500,000, assuming a competitive annual IHC rate of 25% (within the 15%–30% industry range).

If the air freight base rate is $5,000 higher than the sea freight base rate, the total financial saving, factoring in the reduced IHC, results in a net positive outcome of approximately $5,274. The savings generated by reduced IHC often exceeds the difference in base transport costs, transforming air freight from a premium expenditure into a sophisticated cash flow optimization strategy. This speed allows for quicker inventory turnover, improving overall business liquidity, and validating the strategic choice for high-value density goods.

Table: Total Landed Cost Modeling: Air vs. Sea (Hypothetical High-Value Shipment)

| Factor | Air Freight (5 Days) | Sea Freight (35 Days) | Financial Differential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shipment Value | $500,000 | $500,000 | N/A |

| Annual IHC Rate | 25% | 25% | N/A |

| IHC Cost (Per Day) | $342.47 | $342.47 | N/A |

| Total IHC Cost (Transit Period) | $1,712 | $11,986 | $(10,274) |

| Estimated Base Freight Rate | $15,000 | $10,000 | $5,000 |

| Total Landed Cost (TLC) | $16,712 | $21,986 | Net Saving: $5,274 (via Air) |

Note: This simplified model excludes other surcharges, insurance, and duties.

C. Risk, Reliability, and Insurance Cost Comparison

Risk and reliability contribute directly to TLC through insurance premiums and the cost of potential stockouts or damage. Air freight generally offers higher security standards due to rigorous airport screening and tighter handling protocols, making it the preferred mode for sensitive, fragile, or high-value items.

Conversely, sea freight, particularly on long-distance voyages involving multiple port transfers, carries an inherently higher risk of damage from the elements, container handling errors, theft, or piracy.

These risk differentials are reflected in insurance costs. Marine cargo insurance (sea) typically ranges from 0.2% to 2% of the goods’ total value. Air freight insurance rates generally average between 0.3% and 1% of cargo value. While air freight may start at a higher baseline premium, the necessary, comprehensive coverage needed to mitigate sea freight’s higher risk exposure—particularly against Named Perils—can push the marine premium into the upper ranges. The high reliability and schedule frequency of air freight further mitigate stockout penalties, which for fast-moving, high-demand products, often dwarf minor differences in transportation expenditure.

V. Strategic Recommendations for Cost Optimization in 2025

Optimal cost savings in 2025 depend entirely on aligning shipment characteristics with the Total Landed Cost framework.

A. Segmented Decision Framework (Break-Even Analysis)

Mode selection must be dictated by product value density, volume, and urgency. The following matrix summarizes the break-even dynamics:

| Shipment Characteristic | Recommendation | TLC Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Volume < 2 CBM / < 500 kg | Air Freight (or LCL) | Air base rates are competitive in this range; superior speed and reliability reduce IHC/risk. |

| Volume > 5 CBM (Standard) | Sea Freight (FCL preferred) | Ocean cost efficiency scales exponentially with volume; fixed FCL rate minimizes per-unit cost. |

| High Value Density (e.g., Electronics, Pharma) | Air Freight | Transit time reduction significantly reduces high capital carrying costs (15%–30% annual IHC). |

| Perishable or Time-Critical Goods | Air Freight (Non-negotiable) | Transit time is critical; high reliability and flexible scheduling allow rapid market response. |

| Medium Volume (2-5 CBM) / Volatile Route | TLC Modeling (Scenario Analysis) | This range is the new grey area; LCL complexity and high sea surcharges require precise TLC calculation. |

B. Procurement and Visibility Strategies

To minimize costs in this volatile environment, companies must develop agile and adaptable supply chains.

- Optimizing Base Rates and Contracts: Shippers should secure long-term contract capacity for 70%–80% of forecasted volume. This practice stabilizes the freight budget and mitigates exposure to sharp volatility in the spot market, which is prone to sudden spikes. Spot markets should be utilized selectively for opportunistic purchasing or managing unexpected surges. When utilizing digital marketplaces or freight forwarder platforms, shippers must account for typical 15%–25% markups on raw carrier rates.24

- Mitigating Surcharges and Risk: Given the rapid fluctuations in fuel prices and new regulatory costs, shippers must proactively audit the Bunker Adjustment Factor (BAF) and other surcharges included in quotes. Furthermore, Incoterms (e.g., FOB, CIF, DDP) must be used strategically to define clear responsibility for terminal handling charges (THC) and customs duties, thereby minimizing hidden fees that can add $200–$500+ per container. Regarding ocean disruptions, maintaining a strategic buffer stock (3–4 months) is advised to hedge against future shipping volatility and congestion.

- Enhancing Supply Chain Agility: Investment in end-to-end supply chain visibility through technology—such as IoT sensors, AI-powered analytics, and cloud platforms—is increasingly critical. These tools enable shippers to consolidate transport and inventory data into a single view, allowing for rapid identification of ocean delays, prompt adjustments to routing (e.g., switching to air where necessary), and real-time risk management before disruptions impact customers or escalate costs.

C. Future Outlook: Environmental and Technological Alignment

The regulatory environment, particularly the EU ETS, indicates that sea freight will face persistent upward cost pressure on environmental grounds. Long-term cost optimization strategies must therefore integrate financial analysis with environmental impact. While sea freight generates fewer $\text{CO}_2$ emissions per kilogram transported compared to air freight , the accelerating environmental compliance costs confirm that the era of ultra-cheap ocean shipping is concluding, forcing shippers to seek efficiencies through technology, advanced forecasting, and multimodal strategies.

VI. Conclusions

The question of which mode, sea or air freight, saves more money in 2025 is contingent upon the shipment’s value density and the company’s capital carrying cost percentage.

- Sea freight (FCL) provides the fundamental savings for high-volume, low-value density goods due to economies of scale. However, this cost advantage is increasingly jeopardized by extreme market volatility, mandatory regulatory cost increases (EU ETS), and unpredictable surcharges. Cost saving here requires disciplined contract management and active auditing of accessorial fees.

- Air freight provides strategic savings for high-value goods by minimizing capital lockup. When annual Inventory Holding Costs are high (15%–30%), the financial advantage gained by reducing transit time from 35 days to 5 days often outweighs the higher base rate. For such shipments, the air premium is justified as a strategy for cash flow optimization and risk mitigation against volatile tariffs or supply chain disruptions.

- The critical decision point is in the Total Landed Cost (TLC) model. For shippers of medium-value goods in the 2–5 CBM range, meticulous TLC calculation incorporating IHC is essential. Failure to account for the financial burden of time and the accumulating cost of regulatory and handling surcharges will lead to suboptimal mode selection and preventable financial losses in 2025.