In global logistics, the concept of a dry port has gained increasing attention as supply chains become more complex and congestion at coastal ports intensifies. While the term is widely used, its meaning is often misunderstood. A dry port is not simply a warehouse located inland, nor is it a conventional logistics park. Instead, it represents a strategic extension of a seaport’s operational capacity into inland territory.

A dry port can be defined as an inland intermodal terminal directly connected to one or more seaports by high-capacity transport corridors—primarily rail—where containers are transferred, stored, cleared by customs, and redistributed to regional markets. Unlike traditional inland depots, dry ports are functionally integrated into the port system itself. This integration allows port-related activities to be relocated inland, easing pressure on coastal infrastructure.

Understanding this distinction is essential for logistics decision-makers, because dry ports influence routing strategies, cost structures, and network resilience at a systemic level.

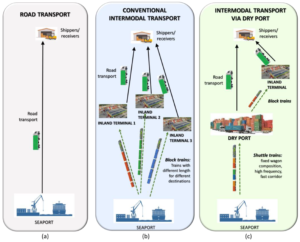

Visual comparison of three freight transport models: (a) road-only transport from seaport to shippers, (b) conventional intermodal transport using multiple inland terminals, and (c) intermodal transport via a dry port using block and shuttle trains. The diagram illustrates how dry ports reduce seaport congestion, consolidate inland flows, and improve rail-based logistics efficiency.

Source: Adapted from Applied Sciences, MDPI — Dry Port and Intermodal Transport System Analysis.

Why Dry Ports Have Become Essential in Modern Logistics

Global trade volumes continue to rise, yet physical expansion around major seaports remains limited. At the same time, vessel sizes have increased significantly, leading to intense peaks in container discharge. These structural pressures create congestion, longer dwell times, and higher operational risk at coastal terminals.

Dry ports exist as a response to these constraints.

By enabling rapid evacuation of containers from seaports via rail, dry ports shift congestion away from the coastline and redistribute cargo closer to inland demand centres. As a result, ports can focus on vessel handling efficiency, while inland terminals absorb storage, clearance, and distribution functions.

Moreover, dry ports allow logistics networks to scale without relying solely on coastal expansion—an increasingly unrealistic option in many regions.

Dry Port vs. Inland Warehouse: Understanding the Difference

One reason many dry port articles fail to rank well is the lack of clarity between dry ports and standard inland warehouses. High-ranking logistics platforms clearly separate these two concepts.

An inland warehouse is primarily designed for storage and local distribution. A dry port, however, operates as an intermodal and administrative gateway.

The defining characteristics of a dry port include:

-

Direct rail connection to seaports

-

On-site customs and clearance facilities

-

Intermodal transfer between rail and road

-

Integration with port community systems

-

Function as a controlled cargo entry and exit point

Because of these features, dry ports actively shape freight flows rather than simply receiving cargo after routing decisions are made.

Dry Port vs. Traditional Inland Warehouse

| Feature | Dry Port | Inland Warehouse |

|---|---|---|

| Rail connection to seaport | Yes (core function) | Not required |

| Customs clearance on site | Yes | Usually no |

| Integration with port systems | Yes | No |

| Role in routing decisions | Strategic | Limited |

| Congestion relief for seaports | Direct | Indirect |

| Typical cargo volume | High, containerised | Variable |

Source: World Bank, UNESCAP, and global port authority frameworks

The Central Role of Rail in Dry Port Operations

Rail connectivity is the foundation of every effective dry port. Without reliable, high-capacity rail links, inland terminals cannot perform port-related functions at scale. Rail enables containers to move quickly away from congested seaports, reducing reliance on long-haul trucking and improving schedule predictability.

Compared to road transport, rail offers:

-

Lower emissions per ton-kilometre

-

Greater efficiency for high-volume flows

-

Reduced exposure to fuel price volatility

-

Higher reliability over long distances

For this reason, dry ports are often developed alongside national rail strategies and multimodal corridor initiatives. Countries investing in rail infrastructure frequently prioritise dry ports as anchor nodes within inland logistics networks.

Dry Ports and Supply Chain Resilience

Beyond efficiency gains, dry ports significantly enhance supply chain resilience. Modern logistics networks are exposed to frequent disruption, including port strikes, weather events, labour shortages, and geopolitical tension. Concentrating too much activity at a single coastal node increases vulnerability.

Dry ports decentralise risk.

By relocating clearance, storage, and sequencing inland, logistics networks gain flexibility. If congestion or disruption occurs at a seaport, cargo can still be processed and distributed through inland terminals. This redundancy reduces the impact of localized failures and supports continuity during high-volatility periods.

In addition, dry ports allow companies to position inventory closer to consumption zones, improving response time to demand fluctuations.

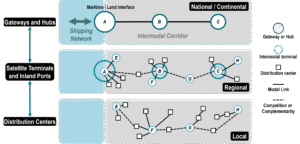

Conceptual diagram of a dry port–centred multimodal logistics network, illustrating how maritime gateways connect to inland ports, satellite terminals, and local distribution centers through rail-based intermodal corridors. This structure highlights the strategic role of dry ports in reducing seaport congestion and improving inland freight efficiency.

Source: Adapted from UNESCAP & World Bank logistics and dry port development frameworks.

Sustainability and the Dry Port Model

Environmental performance has become a central consideration in logistics planning. Rail-based inland transport produces significantly lower CO₂ emissions than long-distance trucking. As a result, dry ports support greener freight strategies by shifting cargo movement toward lower-emission modes.

Dry ports contribute to sustainability by:

-

Reducing truck congestion near seaports

-

Lowering overall fuel consumption

-

Supporting multimodal routing optimisation

-

Aligning with ESG and carbon-reduction targets

As environmental regulations tighten, dry ports are increasingly viewed as compliance-enabling infrastructure rather than optional investments.

Where Operators Like Arta Rail Fit into the Dry Port Ecosystem

While dry ports are global infrastructure concepts, their effectiveness depends on the quality of inland transport execution. Rail–road coordination, scheduling reliability, and corridor management determine whether a dry port functions as a true extension of the seaport or merely as a storage site.

This is where inland logistics operators such as Arta Rail play a practical role. By managing rail–road corridors and multimodal inland connections, Arta Rail supports the operational backbone that allows dry ports to function efficiently. Their role is not to replace seaports, but to enable smooth inland integration—ensuring containers move reliably between coastal gateways, dry ports, and regional markets.

Such inland connectivity is especially critical along long-distance and cross-border corridors, where predictable rail performance underpins the success of dry port systems.

Why Understanding Dry Ports Matters for Logistics Decision-Makers

For shippers, freight forwarders, and network planners, understanding dry ports is no longer optional. Decisions related to routing, cost control, emissions reduction, and resilience are directly influenced by how effectively dry ports are integrated into logistics networks.

Dry ports are not merely infrastructure projects. They are strategic instruments that reshape the geography of global trade.

In the next section, we will examine the key benefits of dry ports, including cost efficiency, congestion reduction, sustainability advantages, and operational resilience—and how these benefits translate into measurable logistics performance.

2. Core Functions and Strategic Benefits of Dry Ports

Dry ports are not passive inland yards. In modern logistics systems, they operate as active control points that redistribute cargo flows, stabilise inland transport, and reduce pressure on coastal infrastructure. As global ports face capacity limits, labour constraints, and congestion cycles, dry ports have become essential components of resilient supply chains.

Instead of concentrating all logistics activity at the coastline, dry ports move critical functions inland—closer to manufacturers, distributors, and consumption centres. This structural shift improves efficiency across the entire transport chain.

2.1 How Dry Ports Reduce Seaport Congestion

Seaport congestion is often caused by limited yard space, high truck volumes, and slow container evacuation. Dry ports directly address these bottlenecks by enabling fast inland evacuation via rail.

Key mechanisms include:

-

Direct rail transfer of import and export containers from seaport terminals

-

Reduced container dwell time at coastal yards

-

Lower truck congestion around port gates

-

Improved vessel turnaround and berth productivity

Instead of containers waiting at expensive coastal terminals, they are moved inland in block or shuttle trains, where clearance and distribution occur under less time pressure.

Impact of Dry Ports on Seaport Performance

| Indicator | Without Dry Port | With Dry Port Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Container dwell time | High | Significantly reduced |

| Truck congestion | Severe | Controlled |

| Yard utilisation | Overloaded | Balanced |

| Vessel turnaround | Slower | Faster |

| Port scalability | Limited | Extended inland |

Rail-based evacuation allows seaports to transfer containers inland quickly, reducing congestion and improving terminal throughput. Source: UNESCAP / World Bank dry port development studies.

2.2 Rail Utilisation and Multimodal Balance

Dry ports act as rail demand concentrators. Rail transport becomes efficient only when cargo volumes are aggregated—and dry ports are designed precisely for this role.

Their contribution to multimodal balance includes:

-

Consolidation of dispersed cargo into rail-friendly volumes

-

Regular, scheduled rail services instead of ad-hoc trucking

-

Clear separation between long-haul rail and last-mile road transport

-

Lower exposure to fuel price volatility

As a result, road transport is repositioned as a last-mile solution, not the backbone of long-distance inland freight.

Transport Mode Role in Dry Port–Based Logistics

| Transport Mode | Primary Role | Typical Distance |

|---|---|---|

| Rail | Long-haul inland movement | 300–1,500 km |

| Road | Last-mile and regional distribution | < 150 km |

| Sea | Intercontinental transport | Global |

| Multimodal | Integrated optimisation | End-to-end |

2.3 Inland Customs Clearance and Administrative Relief

Customs clearance is one of the most underestimated sources of delay in international logistics. Dry ports help decentralise this process by shifting clearance inland.

Operational benefits include:

-

Reduced administrative congestion at seaports

-

Faster cargo release after vessel discharge

-

Easier coordination between shippers and customs authorities

-

Improved predictability for inland distribution planning

By separating physical unloading at the port from administrative processing inland, logistics systems gain flexibility and stability.

2.4 Cost Efficiency Across the Supply Chain

Dry ports generate cost savings at multiple levels:

-

Lower inland transport costs through rail consolidation

-

Reduced storage fees at high-cost seaport terminals

-

Better equipment utilisation (wagons, trucks, containers)

-

Lower inventory buffers due to improved schedule reliability

For exporters and importers, these savings translate into more predictable landed costs and stronger competitiveness.

2.5 Supporting Inland Logistics Hubs and Regional Growth

Dry ports often evolve into full-scale logistics hubs offering:

-

Warehousing and cross-docking

-

Packaging and labelling

-

Light assembly and postponement services

-

Distribution centre integration

This attracts logistics providers, manufacturers, and e-commerce operators to inland regions—supporting economic decentralisation and job creation.

2.6 Where Operators Like Arta Rail Add Real Value

Infrastructure alone does not make a dry port successful. Performance depends on coordination, scheduling, and corridor management.

Operators such as Arta Rail play a practical role by:

-

Aligning rail schedules with seaport discharge windows

-

Managing rail–road transfers at inland terminals

-

Supporting multimodal routing across long-distance corridors

-

Maintaining reliability during congestion or disruption

By connecting predictive planning with physical execution, Arta Rail helps transform dry ports into functional extensions of maritime gateways.

3. Strategic Role of Dry Ports in Global Logistics Networks (2025–2030)

As global trade volumes continue to rise and coastal ports face structural limits, dry ports are no longer optional infrastructure. They are becoming strategic nodes in global logistics networks—reshaping how cargo moves, where value is created, and how resilience is built across supply chains.

Instead of viewing logistics as a linear port-to-destination flow, modern networks operate as distributed systems. Dry ports sit at the centre of this transformation.

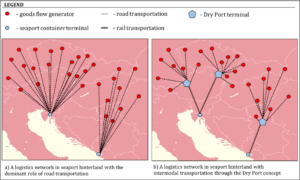

3.1 From Coastal Bottlenecks to Distributed Networks

Traditional port-centric logistics models concentrate too much activity at the coastline. This creates vulnerability when ports face disruption from congestion, labour shortages, weather events, or geopolitical risk.

Dry ports enable a different model:

-

Cargo is cleared and distributed inland

-

Seaports focus on vessel handling efficiency

-

Inland corridors absorb volatility

-

Transport capacity is balanced across regions

This shift reduces systemic risk and improves scalability without requiring constant port expansion.

Centralised vs Distributed Logistics Models

| Feature | Port-Centric Model | Dry Port–Integrated Model |

|---|---|---|

| Congestion risk | High | Distributed |

| Inland connectivity | Limited | Strong |

| Rail utilisation | Low | High |

| System resilience | Fragile | More resilient |

| Expansion cost | Very high | Lower (inland-based) |

3.2 Enhancing Supply Chain Resilience and Risk Management

Resilience is now a core performance metric in logistics. Companies are no longer optimising only for cost—they are optimising for continuity.

Dry ports strengthen resilience by:

-

Creating alternative inland routing options

-

Reducing dependence on a single coastal gateway

-

Allowing faster rerouting during disruptions

-

Supporting buffer capacity away from ports

When maritime routes are disrupted, inland terminals provide operational flexibility that coastal ports cannot offer.

This is particularly valuable for multimodal corridors, where rail-based dry ports act as stable anchors in volatile global networks.

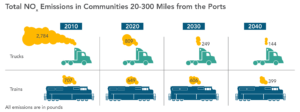

3.3 Sustainability and Emissions Reduction

Environmental performance is another major driver behind dry port expansion. Rail-based inland transport significantly lowers emissions compared to long-haul trucking.

Key sustainability benefits include:

-

Lower CO₂ emissions per ton-kilometre

-

Reduced truck traffic around urban ports

-

Better energy efficiency through block trains

-

Support for ESG and carbon-reporting goals

Dry ports also enable green corridor development, where rail, energy-efficient terminals, and digital planning work together.

Environmental Impact of Dry Port Integration

| Metric | Without Dry Port | With Dry Port |

|---|---|---|

| Long-haul trucking | High | Reduced |

| Rail share | Low | Increased |

| CO₂ intensity | Higher | Lower |

| Urban congestion | Severe | Reduced |

| ESG alignment | Weak | Stronger |

Dry ports enable sustainable freight by shifting long-distance cargo from road to rail, reducing emissions and congestion. Source: International Transport Forum (ITF).

3.4 Economic and Regional Development Impact

Beyond transport efficiency, dry ports act as economic multipliers. Once established, they attract logistics providers, manufacturers, and distributors.

Common outcomes include:

-

Growth of inland logistics clusters

-

Job creation in transport and warehousing

-

Reduced pressure on coastal cities

-

Balanced regional development

Dry ports often evolve into logistics cities, integrating transport, storage, value-added services, and industrial activity.

3.5 Why Rail-Centric Operators Matter

Dry ports succeed only when supported by reliable rail operations. This is where specialised rail and multimodal operators play a critical role.

Operators like Arta Rail contribute by:

-

Managing rail corridors connecting ports to inland terminals

-

Coordinating block and shuttle train services

-

Aligning inland schedules with maritime flows

-

Supporting cross-border rail transit

Their role ensures that dry ports are not isolated facilities but fully integrated nodes within international logistics corridors.

3.6 Dry Ports in Eurasian and Emerging Corridors

Dry ports are especially critical in long-distance trade corridors across Eurasia, Central Asia, and landlocked regions.

Their strategic value includes:

-

Bridging maritime and inland trade routes

-

Supporting North–South and East–West corridors

-

Improving access for landlocked economies

-

Enhancing cross-border rail connectivity

In these regions, dry ports are not just efficiency tools—they are enablers of global trade participation.

Why Dry Ports Are a Structural Necessity

Dry ports are no longer a supporting feature of global logistics. They are a structural necessity in a world defined by congestion, sustainability pressure, and geopolitical uncertainty.

By redistributing cargo flows inland, strengthening rail utilisation, reducing emissions, and improving resilience, dry ports redefine how logistics systems scale.

For logistics operators and shippers alike, integrating dry ports into multimodal strategies is not about future planning—it is about maintaining competitiveness today.

For companies working across long-distance corridors, rail-based solutions supported by experienced operators such as Arta Rail offer a practical path toward more stable, resilient, and sustainable global supply chains.